Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

Exhibitions Archive

AZ08. Resurrection and Descent into Hell

Russian, Palekh School, circa 1800

Panel: 21 x 21 cm; 2.4cm thickness![hideselects= [On] header =[Convert size] body = [Click here to show the size in inches] Click here to convert metric size to imperial](images/inches.gif)

Condition: the panel was once surrounded by a border with the Twelve Feasts of the Church. Some of the gold on the haloes and the ground is abraded.

Inscriptions: Old Slavonic inscriptions identify the various scenes depicted.

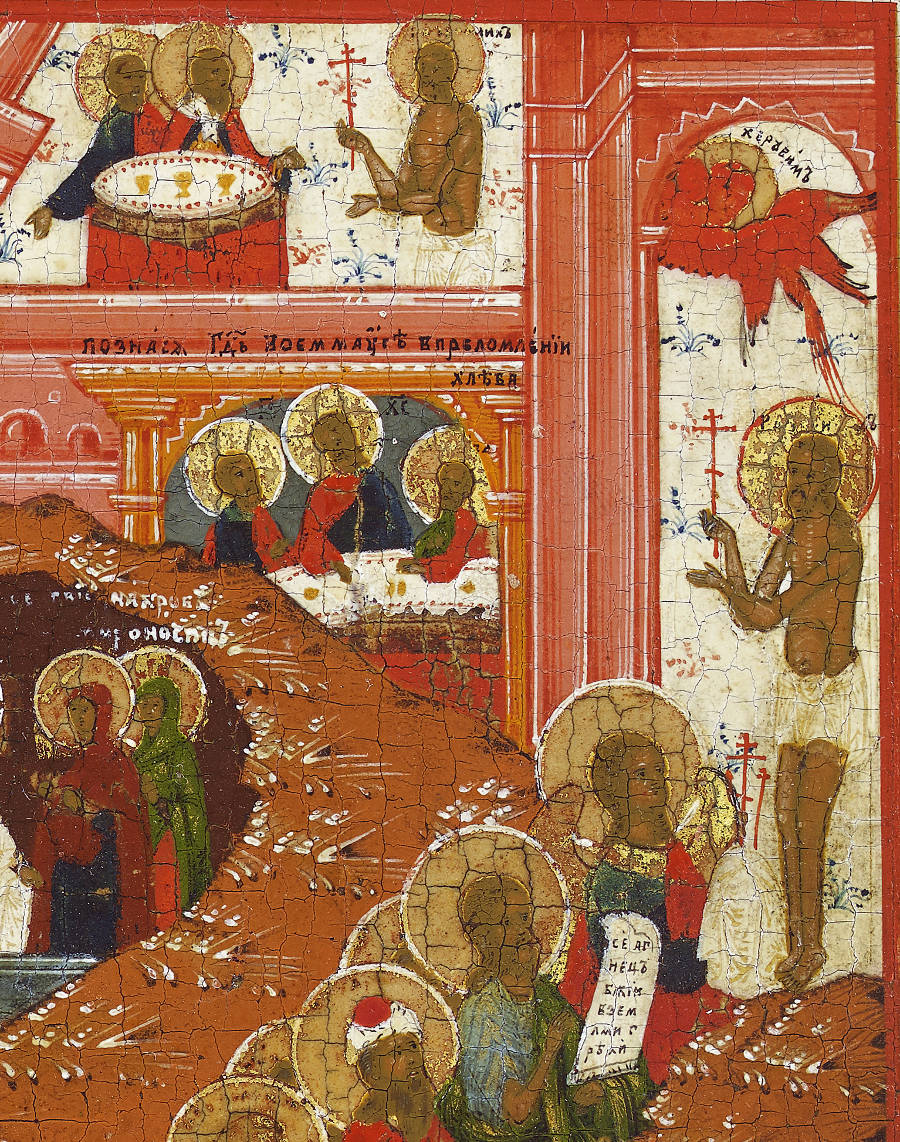

No. 8. Detail 1.

No. 8. Detail 2.

No. 8. Detail 3. The mouth of hell from which exit the just.

No. 8. Detail 4. The Garden of Paradise, the Good Thief, the Trinity, the Myrrh-Bearing Women and the Procession of the Just

No. 8. Detail 5. The Doubting of Thomas, the Crucifixion, the Entombment, Joseph of Arimathea, the Angelic Host.

No. 8. Detail 6. Christ by the Sea of Galilee

The event depicted in this icon, known in Russian as VOSKRESENIE I SHOSHESTVIE VO AD, in Greek as ANASTASIS and in Old English as the Harrowing of Hell, is the Orthodox Church’s greatest feast. It celebrates Easter, and shows Christ Descending into Hell to rescue Adam and Eve, and by implication all of humanity, from spiritual death; all this representing the general resurrection of humanity.

Between the 11th and the 15th centuries the classic Byzantine images illustrate the essential elements as one sees in the mosaic of Hosios Loukas and the Temple Gallery’s masterpiece by Angelos (Fig. 1, 2).

Fig. 1. Mosaic, Hosios Loukas, 11th century. |

Fig. 2. Icon by Angelos, c. 1440 |

In later Russian icons such as the present example, the imagery is extended and elaborated. These changes are thought to have developed under the influence of western medieval art; particularly the wall paintings of the Last Judgment on the interior west wall of 12th century churches. The most magnificent example is at the Cathedral of Torcello, in the Venetian Lagoon (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The Western Wall of Torcello, late 11th – early 12th century

We see, in the lower-left corner, the Jaws of Hell from which Adam and Eve and all those who are saved emerge, including kings David and Solomon (identifiable by their crowns), St John the Baptist and other Old Testament figures. The procession winds upwards towards the Gates of Paradise (upper right corner). There, the Good Thief leads the procession and is preceded by a six-winged seraph. Within Paradise, depicted as a walled garden, we see that the Good Thief has entered and joins Enoch and Elijah (Old Testament prophets who had bodily entered Paradise). The Supper at Emmaus is below the wall, where the resurrected Christ reveals himself to two disciples. In the lower right, we see Christ calling the Apostles by Lake Galilee. In the upper left is the Crucifixion and, in the corner, the Doubting of Thomas. Just below is the Entombment and next to it the Shroud and the Empty Tomb with Joseph of Arimathea. The host of angels proceeds diagonally down below the Entombment, all looking towards the Archangel Michael, who beats the Devil. Christ is shown twice: Descending into Hell and Ascending into Heaven. At the centre, just below the Risen Christ, are the Myrrh-bearing women and the angel indicating the Empty Tomb.

All the vignettes illustrate New Testament accounts while the main event, the Descent into Hell, the Resurrection and the Procession of the Just, is based on the apocryphal, and today little known, Book of Nicodemus1. Another significant older apocryphal source, dating perhaps from the first century and from the immediate entourage of John the Evangelist is the Odes of Solomon. In Ode Forty-Two we hear Christ speaking:

Sheol (Hades) saw me and was shattered, and Death ejected me and many with me.

I have been vinegar and bitterness to it, and I went down with it as far as its depth.

Then the feet and the head it released, because it was not able to endure my face.

And I made a congregation of living among his dead; and I spoke with them by living lips; in order that my word may not be unprofitable.

And those who had died ran towards me; and they cried out and said, Son of God, have pity on us.

And deal with us according to Your kindness, and bring us out from the bonds of darkness.

And open for us the door by which we may come out to You; for we perceive that our death does not touch You.

May we also be saved with You, because You are our Saviour.2

The icon, an astonishingly spiritual and artistic tour de force for such a small space, is a compendium of the events of the death and resurrection of Christ, the theology that helps bring the symbolic events to our consciousness through image rather than word.

Palekh is a large village to the northwest of Moscow. Since the eighteenth century, several villages in Russia, a bit like rug-making communities in Anatolia, devoted themselves entirely to the production of fine icons. The impulse came from Old Believers, the schismatic sect of the 17th century who fanatically preserved old traditions of church ritual and icon painting from western influences. Fedoskino, perhaps more known for painted lacquer boxes, and Mstera are also celebrated but Palekh was the largest and most acclaimed. The fame of the school comes from the extreme delicacy and refinement of the craftsmanship and skills of the painters. Their brilliant, miniature style developed out of the paintings of the Stroganoff School in the 17th century. The Palekh school owes its complex landscapes and fine figures to the Stroganoff school as well exemplified in this icon. During the Soviet period (1917—1989), the Palekh workshops survived by the continued production of papier-maché boxes lacquered in black and decorated with finely painted Russian fairy stories. ‘Palekh boxes’ are widely known and collected in their own right. The boxes employ the same use of bright tempera, painted over a black background. Today once again, icons are being painted in Palekh.

Even by Palekh standards the present example is unusually fine not only for its extraordinary artistic achievement but also as an expression of understanding and wisdom. Detail 1, for example, in the tender and meaningful looks and gestures of the three figures, expresses a comprehension of the event’s profound spirituality. The artist, without compromising the conventions of the form, has provided the living mystical content. The icon therefore is likely to come from the revival taking place in 19th century Russia referred to as ‘the Russian Religious Renaissance’ Paul Ladouceur writes of ‘the mystical theology of St Seraphim of Sarov [and] the revival of hesychastic spirituality’3.

Fig. 4. Back of Panel

Footnotes:-